Some Stats on Fraud Training

Looking for some benchmarking data for how you should structure your anti-fraud training program and what it should contain? Fear not, a new survey from the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners has you covered.

The ACFE published its survey over the weekend, after polling more than 1,700 anti-fraud professionals around the world earlier this year. The report offers insights on who does or doesn’t get fraud training in large organizations, what that training addresses, and how anti-fraud leaders evaluate the success of their program to assure it stays relevant. Which is good stuff to know, given that other AFCE research shows that fraud risk during the age of covid has gone nowhere but up.

The good news is that 71 percent of respondents said their businesses have some sort of fraud awareness training program. That’s great, since the ACFE estimates that fraud costs the global economy $4.5 trillion each year, and that the average loss per fraud in 2019 was $1.51 million. Whatever your fraud training program costs, it won’t cost that much; so the investment is worthwhile.

On the other hand, 29 percent of respondents said their businesses didn’t have a fraud awareness program. More alarming, however: the single most common reason for not having a program, cited by more than one-third of this group, was that fraud training was “not part of the organizational culture.”

Do the math, and that’s roughly 11 percent of all respondents saying fraud awareness training isn’t part of their corporate culture. I wonder what planet those people live on.

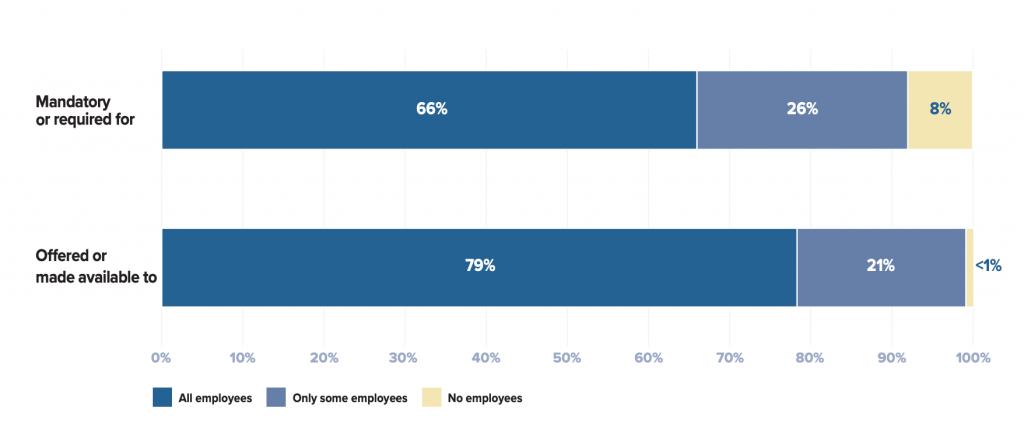

Also, more than 90 percent of organizations make fraud awareness training mandatory for at least some employees, and 66 percent make it mandatory for all employees. And virtually every organization offers fraud training, even if the organization doesn’t specifically require it. See Figure 1, below.

Source: ACFE

Focus & Recipients of Fraud Training

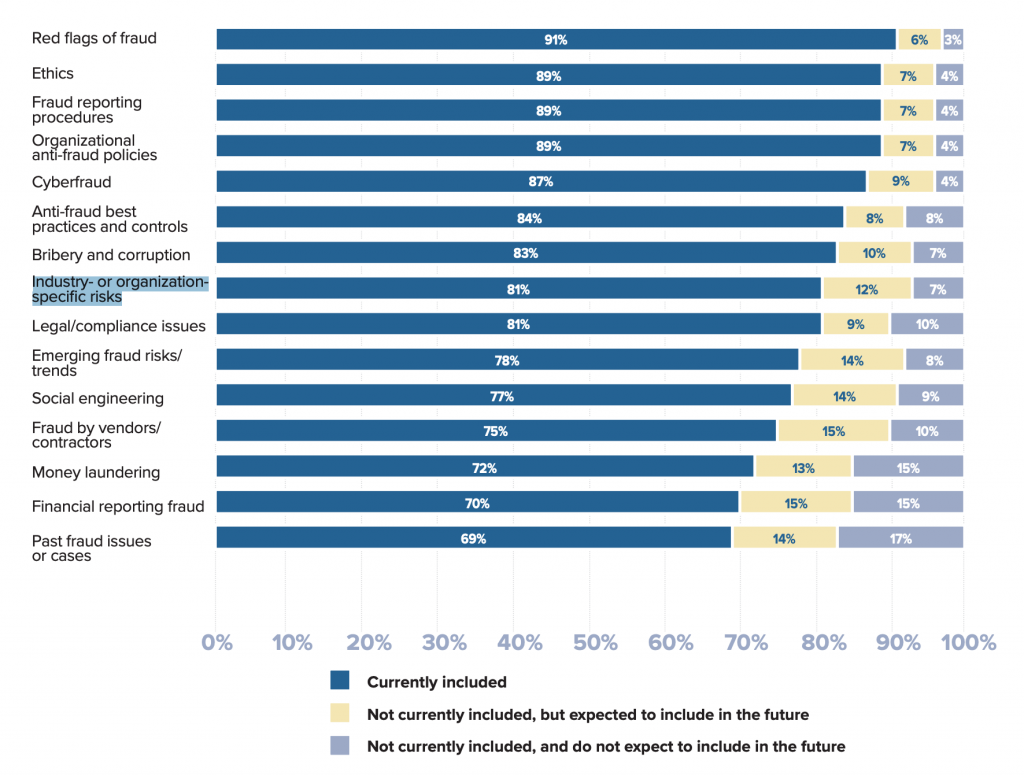

The most common training subjects were the red flags for potential fraud, followed by ethics and fraud reporting procedures. (See Figure 2, below.) That strikes me as right. For most employees, the most important thing is to give them enough sophistication to spot potential fraud, the ethical impulse to alert somebody to their suspicions, and the knowledge of how to file that report. That’s all they need to do. The rest is your job.

Source: ACFE

The only concern I have is about industry- or organization-specific risks, halfway down the chart above and highlighted in blue. Only 81 percent of respondents include fraud training tailored to their business, compared to the 90-ish percent who offer training on red flags and ethics.

Eighty-one percent is still high, but it is appreciably less. So it’s food for thought as you design your own fraud awareness program. Who in your organization does need fraud training tailored to your specific operations? People in accounting or financial analysis, clearly; perhaps also those in procurement or sales. Are they getting that training? Is the training of sufficient quality?

Let’s remember that the Justice Department’s guidance on effective compliance programs does urge specialized training for “gatekeepers” such as folks in fraud-sensitive roles:

What, if any, guidance and training has been provided to key gatekeepers in the control processes (e.g., those with approval authority or certification responsibilities)? Do they know what misconduct to look for? Do they know when and how to escalate concerns?

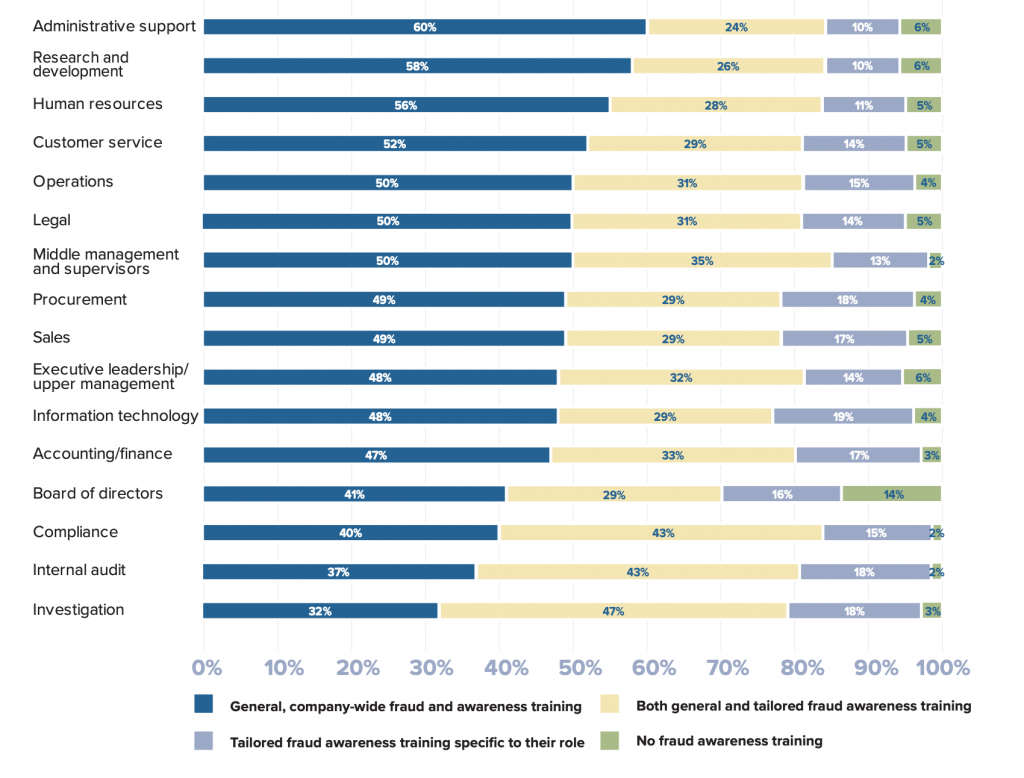

The ACFE report does address that point, too. Figure 3, below, shows various employee groups, and how many received general or tailored fraud training within each group.

Source: ACFE

As we can see (if we squint a bit), a fair number of businesses do provide tailored training to gatekeeper groups, such as accounting, compliance, internal audit, and investigation teams. Still, I’d like to see higher numbers for all of those groups.

Who Doesn’t Get Training

Who doesn’t get fraud awareness training? More than any other group, the board of directors. Fourteen percent of respondents said they provide no training to board directors, more than twice as many as any other group.

I’m of mixed emotions about that statistic. It’s true that board directors are supposed to be sophisticated minds, who should already understand the organization’s industry and risks — including fraud risk. The overriding need for directors is that they bring skepticism to the financial reports, more than detailed knowledge of fraud scams.

On the other hand, this also means that board directors rely more on the accuracy of financial statements. Put simply, the less your directors know about fraud, the more they need to trust that fraud risk is already sufficiently addressed by your internal controls and the external auditor.

It’s also interesting to see the sheer amount of fraud awareness training employees get, or the lack thereof. Sixty-one percent of respondents said their employees spend two hours or less on fraud training every year. Eleven percent said employees aren’t required to get any fraud training at all.

Again, those numbers are food for thought. It’s probably fine for many employees to take a few 30-minute online training courses over the course of the year (78 percent said they offer online training; 50 percent offer in-person instruction). At least some portion of your managers and Second Line of Defense employees, however, would do well to get more.