Boeing’s Report on Speakup Culture

Today we return to Boeing and the various steps it’s been taking to improve its safety and compliance culture. The company discussed those steps in an “aerospace safety report” Boeing released a few weeks ago, with lots of material on how Boeing is trying to improve its speakup culture. Let’s take a look.

Boeing has been publishing these aerospace safety reports since 2022, presumably as part of its first settlement with the Justice Department in 2021 for two Max 737 crashes in the late 2010s. That deferred-prosecution agreement was set to expire in 2024, but just before expiration Boeing suffered another debacle with a door that blew out mid-flight on an Alaska Air flight because the door had been missing bolts to keep it secure. Prosecutors promptly declared the DPA breached.

More legal wrangling followed, and in late May the two sides struck a second deal: a two-year non-prosecution agreement, no compliance monitor, and a promise that Boeing will spend another $445 million on compliance program improvements. That deal still awaits final approval from a federal judge, and the agreement might yet unravel because of the June 12 Air India crash that killed 241 people, which involved a Boeing Dreamliner.

The cause of that crash remains unclear, but obviously any mechanical failures will be damning for Boeing — which brings us back to the company’s aerospace safety report. The whole point of these reports is to demonstrate that Boeing has changed its safety culture for the better. So how does a company with 178,000 employees and a byzantine global supply chain do that?

First, the Internal Hotline

The first section of the report talked about safety culture and improvements Boeing made last year to its internal hotline.

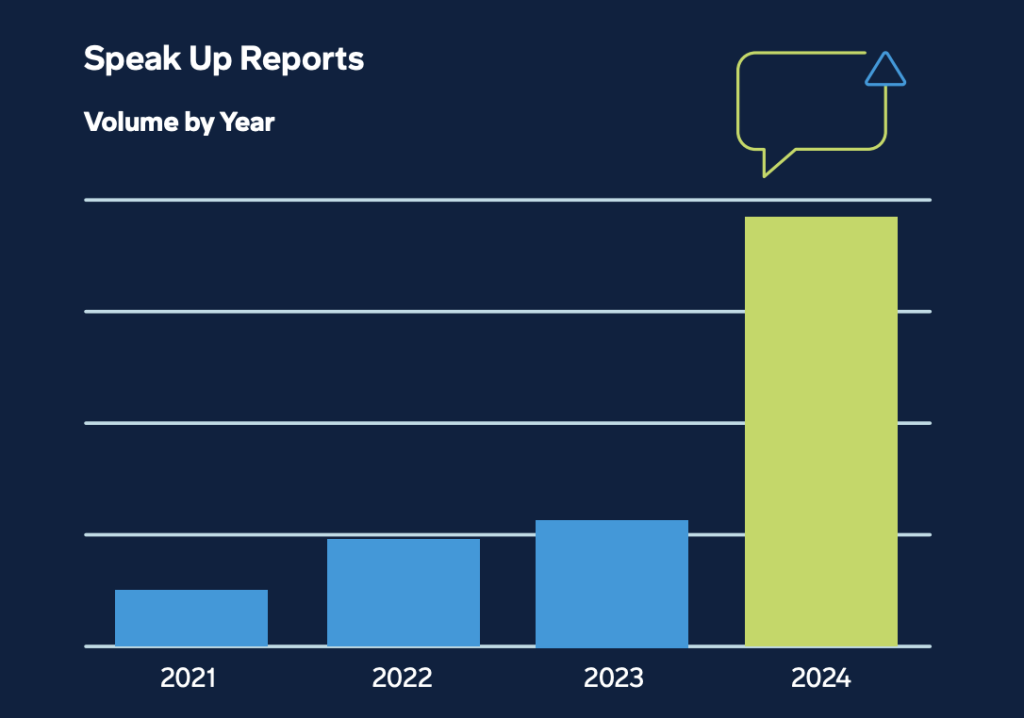

The good news is that Boeing saw the number of reports received on its hotline jump 220 percent from 2023 to 2024. Boeing didn’t disclose precisely what that number was, but we can see (in Figure 1, at right) that report volume did surge dramatically last year compared to prior years in the early 2020s.

Source: Boeing

Why? I suspect it was partly due to that door blow-out in early 2024, which demonstrated that, no, Boeing hadn’t put its safety shortcomings behind it. The door failure lit a fire under management’s rear end to improve internal reporting of safety issues swiftly and sharply.

Boeing also made two tactical improvements to its hotline.

First, it revamped its procedures to improve the confidentiality of the internal reporting system. The new protocol is that when an employee submits a report, the issue is not assigned to the direct manager of that employee. Every report is evaluated by a third person not connected to the employee or manager.

Second, it revamped the interface of the internal hotline to give employees more transparency into the internal reporting system. Every employee who submits a report now gets real-time updates on the status of their submissions, as well as access to a private dashboard where they can review and track their reports. All employees also now have access to a broader array of internal reporting data, including volume of reports received and outcomes of reporting.

These two changes are solid steps forward because they get to the fundamental ingredients for the success of an internal hotline:

- Employees need to feel safe using the system.

- Employees need to believe that when they bring an issue to management’s attention, management will do something.

That’s the whole ballgame for internal reporting, really. If your internal reporting program can’t hit both of those points, employees won’t trust the system and they won’t use it.

What troubles me is that Boeing didn’t already have those elements of trust built into its internal reporting system, when that should be basic block-and-tackle stuff for an organization as large and sophisticated as Boeing.

For example, back in 2019 the Government Accountability Office published a report on whistleblower protections within the Defense Department. That report spotlighted numerous bad practices where a whistleblower’s identity might either leak out by accident, or be uncovered by nosy managers in just a few easy steps. Other studies, white papers, and blog posts have explored the procedural cracks that can undermine an internal reporting system too, and how those cracks should be sealed. This is not new news.

Likewise, the compliance community has talked for years about how a management listen-up culture is the necessary precursor for an employee speakup culture. That is, employees need to “feel heard.” They need to see evidence that when they submit reports, management does something.

More transparency, via dashboards and real-time status updates and data on overall internal reporting systems, is a great way to demonstrate to employees that management hears them.

So I applaud Boeing for taking these steps in 2024, and those steps are paying off. It’s just a shame that these steps weren’t taken long ago.

Second, Better Training and Outreach

All that said, corporate culture does not live on internal reporting alone. Boeing also took new steps on training and outreach to drive a stronger safety culture.

Most notably, Boeing increased the size of its “safety champions program” — functionally the same as those compliance ambassadors we always like to talk about — to more than 1,000 people. Champions went through a five-week virtual training program, which “supports the continuous improvement of Boeing’s [safety culture] while promoting each champion’s professional growth as they promote [safety] principles in their work teams.” Boeing even hosts quarterly alumni meetings to keep champions engaged and aware of the latest developments in the company’s safety and quality program.

A few thoughts here. First, doubling the size of the champions program raises an interesting question: How large should your compliance champions program be?

Like, 1,000 champions for a business of 178,000 employees is a ratio of 1 champion per 178 employees. That ratio seems high to me — but then again, safety is Boeing’s highest risk, and the company hadn’t done a great job managing safety risk before. So perhaps doubling that champions ratio from 1 per 342 employees in 2023 (Boeing had slightly fewer total employees that year) to 1 per 178 in 2024 was warranted.

To determine the proper size for your champions program, you need to consider your primary risks, the potential severity of those risks, your past track record at taming those risks, and your resources to create a cadre of thoughtful, engaged, competent champions.

I also like how Boeing created an alumni network for its champions, so that they still feel connected to the safety program even as that program continues to evolve. That’s an idea that ethics and compliance teams at any large organization would do well to copy.

Boeing also trained 160,000 employees on safety, with an emphasis on identifying and reporting product hazards. The training was role-based, as God and the framers of the Constitution intended; but I was particularly intrigued by the additional training Boeing provided to managers.

Specifically, Boeing offered managers a “discussion guide … to facilitate team sessions about ways to apply the learning. Boeing provided leaders and teams the tools and training needed to foster a culture that prioritizes safety, encourages communication about safety, and focuses on ongoing improvements.”

OK, the anodyne language in that statement would leave any overpriced HR consultant beaming with pride — but when you boil away the fluff, an important point lurks underneath: managers need to know how to foster. They need to know how to create environments where employees truly believe that they and the company are on the same team.

I fear that too often, we overlook that point when talking about training for managers. Yes, managers need training on how to identify potential misconduct, or how to handle a report from employees. But perhaps even more importantly, managers need to be trained on how to create a strong, ethical culture — and a lot of that is knowing how to create social breathing space for employees to talk about ethics.

That might sound corny, and creating those safe spaces might feel corny — but it’s the corny stuff that creates a safe environment for people to speak up. I’m glad to see Boeing attacking the problem.