No, the FCPA Is Not ‘Back’

Folks, we need to have a conversation about all these legal bulletins, marketing emails, and conference agendas declaring that enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices is now somehow “back,” simply because the Justice Department released guidelines the other week explaining how it will consider FCPA enforcement from here forward.

Snap out of it. FCPA enforcement is not back. FCPA enforcement is likely to remain in a coma for a long while.

That does not mean that companies should therefore race to dismantle their FCPA compliance programs, although some dim-witted management teams will insist they should do exactly that — but we do need a more honest assessment of what’s likely to happen here. The new FCPA enforcement guidelines, released by deputy attorney general Todd Blanche on June 9, are only one part of a larger picture that still leaves compliance officers struggling with ambiguity and internal contradictions about what to expect.

Let’s start with Blanche’s guidelines. He defined four factors that the Justice Department will consider before pursuing an FCPA enforcement action:

- Does the misconduct involve drug cartels or other transnational criminal organizations?

- Does the misconduct prevent specific, identifiable U.S. organizations from fair access to compete for business overseas?

- Does the misconduct threaten U.S. national security interests, especially in industries such as defense, critical infrastructure, or intelligence?

- Does the misconduct involve serious misconduct, such as large-dollar bribes or extensive concealment efforts; or relate to more “routine business practices” at lower dollar amounts?

If the answer isn’t yes to at least one of those questions, then prosecutors aren’t going to bother with an investigation. Nor do we outside the department have a clear sense of how much weight prosecutors will give to each of those factors — for example, whether cases involving cartels will be a higher priority than cases involving egregious misconduct. (Although presumably such questions will be highly dependent on the facts of each case.)

But Wait, There’s More

Blanche’s policy memo does give the appearance that FCPA enforcement will continue, but in a more narrowly focused way. Some of his changes are quite reasonable, such as prioritizing serious misconduct or considering whether the foreign government in question is willing to prosecute its own corrupt official.

Except, when you look at the larger picture of what the Justice Department wants to do, you see the weakness lurking behind this FCPA policy memo.

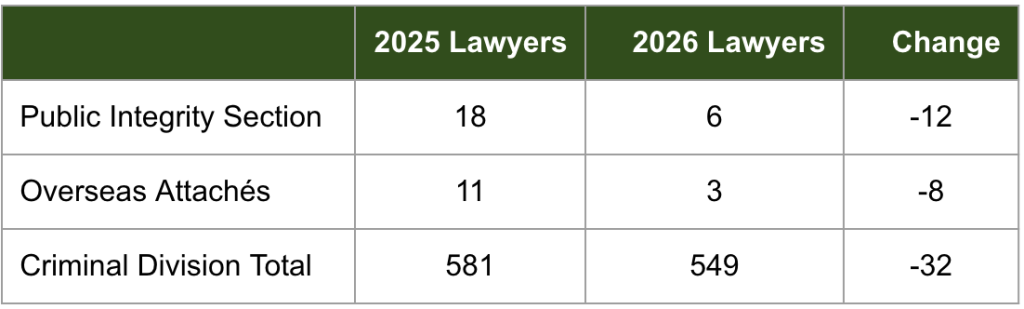

Source: Justice Department fiscal 2026 proposal

The evidence is in the Justice Department’s proposed budget for fiscal 2026, which starts on Oct. 1. The department wants to take an ax to the Criminal Division, with plans to cut the Public Integrity section, the overseas attachés (who work with foreign law enforcement), and the number of lawyers in the Criminal Division overall. (See chart at right.)

Those are the proposed cuts for next year, still to be approved by Congress. They are not to be confused with the layoffs, buyouts, and re-assignments that have already happened this year. That includes extensive cuts to the Fraud Section, the Public Integrity Section, and the Office of International Affairs — all of which play important roles in corporate corruption cases. Now they’re assigned to prosecute undocumented workers, tariff evasion, sanctuary cities, or DEI programs. That’s probably where they’ll stay until they quit.

Altogether, tells us that the Justice Department just isn’t interested in prosecuting the FCPA. In the same way that for years we’ve talked about companies having “paper compliance programs” that exist in document form only, the Justice Department is setting up a paper enforcement program that will hardly ever be pulled off the shelf.

If you want to make a bet on the future of FCPA enforcement, that’s the smart one.

FCPA Issues in the Future

None of this means that companies can or should scrap their anti-corruption compliance programs. That’s exactly the wrong conclusion to draw from the Justice Department’s retreat on FCPA enforcement.

First, there is still the chance the department will prosecute some FCPA enforcement cases. Or that some future Administration might get serious about FCPA enforcement again sometime in the future, which will make a decision today to ignore compliance look terrible. Or that a foreign government might pursue your company for a violation of its own anti-corruption statutes. All those potential legal risks still exist today.

Second are the very real fraud risks that always exist within a large company. You need internal controls to prevent those too, and those anti-fraud controls bear a striking resemblance to FCPA controls.

One recent example is Takeda Pharmaceuticals, which saw one of its technology managers embezzle millions from the company by conspiring with her (now ex) fiancee to set up a bogus consulting group. Just this week the former marketing director of the CFA Institute was indicted for embezzling nearly $5 million from the group over six years doing essentially the same. Both cases involve fictional third parties, improper documentation, insufficient internal controls, and the like. In other words, they were FCPA schemes in all but the foreign official part. A strong anti-corruption compliance program could intercept that.

Third, remember the corrosion that can seep into your business model once you start to pay bribes. Corporate corruption is the business equivalent of heroin: it feels great the first time you do it; then you get addicted and that first-time, feel-good high fades away as you collapse into poor health. The company paying the bribe is diverting cash from other useful purposes like product development; the competing companies that lose the contract thanks to corruption must now divert their cash to bribery too.

So there are still plenty of reasons to keep your anti-corruption compliance program strong and dynamic. But don’t delude yourself that enforcement of the FCPA is one of those reasons. It’s not.