Is ‘Earnings Before Tariffs’ a Thing?

Don’t look now, but Corporate America started filing second-quarter earnings releases in large numbers this week, with many of them mentioning Trump Administration tariffs in some form or another. That raises an intriguing question for all you external reporting and corporate disclosure buffs: Can tariffs somehow be reported as an adjustment to earnings?

This has been on my mind lately because most companies hate tariffs, and would be delighted to find some way to frame those added costs as not their fault. So how might that work in practice? What, if anything, are companies already saying about tariff costs? And how will regulators respond to those disclosures, since President Trump might flip out at any given moment over disclosures he doesn’t like and start ordering investigations?

The short answer is that as a matter of law, companies could at least try to report “earnings before tariffs,” but the accounting logic to get there would take you to some pretty strange places. So companies are reporting the costs of tariffs in other ways that functionally serve the same purpose.

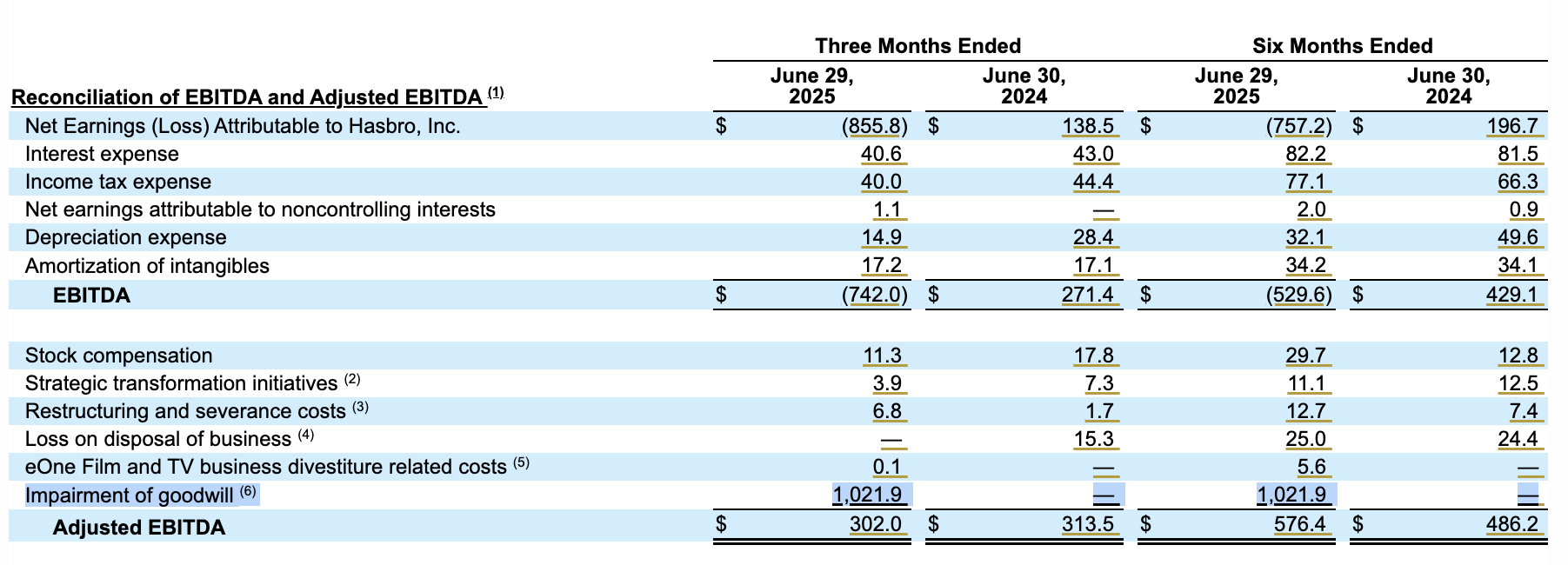

For example, toy-maker Hasbro Inc. filed its Q2 earnings release on Wednesday morning. The company reported a $1.02 billion goodwill impairment charge “following completion of an interim quantitative assessment of goodwill triggered by the implementation of tariffs.” That $1.02 billion charge was responsible for Hasbro reporting a rather ugly $855.8 million net loss for the quarter. If not for the impairment, Hasbro would have reported net income of $166.1 million.

So that’s exactly what Hasbro did: it reported an adjusted net income number that excluded the goodwill impairment charge (plus a few other adjustments too), and miraculously arrived at $302 million in adjusted net income. See Figure 1, below.

So does that count as an “earnings before tariffs” disclosure? It’s legal; plenty of companies report EBITDA, and plenty also tack on other discrete, one-time costs too as adjusted EBITDA.

Then again, it’s also ridiculous; tariffs clearly aren’t a one-time cost. So Hasbro is trying to get this unpleasant new cost of doing business across the financial reporting border by dressing it up as an impairment charge.

The Tricky Headache of Tariff Disclosures

At first glance, one might assume that tariffs are easy to report as adjusted earnings. Companies will know what those amounts are, because they’re paying the tariffs as they buy their components and raw materials. So why couldn’t tariff costs be rolled into EBITDA, earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization? Tariffs are a tax, after all.

Except, no you can’t, because the T in EBITDA refers to income taxes, a point so widely understood by investors that if you rolled tariffs into that number, the Securities and Exchange Commission would probably call you before the end of the day.

So couldn’t you add a second T to EBITDA, expressly for tariffs? EBITDAT, or EBITTDA?

The tricky part there, however, is that income taxes and all the other EBITDA items are adjustments you make at the end of your business operations, after you arrive at an operating profit number. Tariffs are something you pay at the beginning of business operations, before you know what your operating profit number is. The amount you pay for tariffs either gets listed as an operating expense, rolled into the Sales, General & Administrative line; or as part of the cost of goods sold, which ultimately flows into inventory listed on the balance sheet.

My question is this: Couldn’t you report a non-GAAP “adjusted cost of goods sold” to account for tariff costs, and have that adjustment flow through to adjusted operating profit and earnings?

SEC reporting rules require that all non-GAAP disclosures are reconciled back to their nearest GAAP counterpart, but that’s easy: you just reconcile the tariff amounts (which you know, because you paid the taxes) back to cost of goods sold, which is a line item every company reports.

I’ve asked several SEC reporting friends why this idea wouldn’t work. One person gave a pithy, “Now I can’t un-see this, please f—k off” but didn’t deny the basic logic. Others said a disclosure like that would get a comment letter from the SEC via next-day mail — but again, that’s not the same as saying it’s wrong.

I’ve asked several SEC reporting friends why this idea wouldn’t work. One person gave a pithy, “Now I can’t un-see this, please f—k off” but didn’t deny the basic logic. Others said a disclosure like that would get a comment letter from the SEC via next-day mail — but again, that’s not the same as saying it’s wrong.

Critics would say you can’t adjust for tariffs because they’re a regular, ongoing, unavoidable expense; you might as well report “earnings before utilities” or “earnings before paying employees.”

I’m not so sure. Given the erratic nature of the Trump Administration, tariff rates fluctuate wildly from one quarter to the next, and there’s no assurance that tariffs will endure for the long haul. That’s not a regular, ongoing expense. That’s just Trump being incoherent, and companies aren’t wrong to game out scenarios where tariffs don’t last.

What Other Companies Are Saying

I don’t know that we’ll ever see a company so bold as to report “earnings before tariffs.” Instead, they’re waltzing toward that same goal via other methods, such as Hasbro and its $1.02 billion tariff goodwill impairment.

What are other companies saying? As it happens, Radical Compliance and financial data company Calcbench are working on a joint project to track those disclosures. Basically that’s just us reading new earnings releases every morning to see what companies say — and while most companies so far have almost nothing substantive to say, some companies that are affected heavily by tariffs have said quite a bit.

One example is Alcoa, which filed its Q2 earnings release on July 16. The company reported paying $115 million in tariff costs for importing aluminum from Canada into the United States:

In the second quarter 2025, Alcoa incurred approximately $115 million for tariff costs on imports of aluminum to the U.S. from Canada. U.S. Section 232 tariffs were 25 percent from March 12, 2025 until increasing to 50 percent on June 4, 2025.

That’s interesting because Alcoa paid that $115 million while tariff rates were rising — which means tariff costs in Q3 could well be even higher, since the tariff rate went from 25 to 50 percent in June and might stay there.

For perspective, Alcoa also reported cost of goods sold at $2.65 billion for the quarter; the $115 million in tariffs included in that number is 4.3 percent of the total.

Food giant Conagra Brands ($CAG) filed its quarterly results on July 10. It had this to say:

The company also expects cost of goods sold inflation to continue at an elevated level into fiscal 2026. Guidance anticipates core inflation to be approximately 4 percent. In addition, the company expects an impact to fiscal 2026 from previously announced U.S. tariffs … [T]hese tariffs are expected to increase cost of goods sold by approximately 3 percent annually, prior to mitigating actions including accelerated cost savings initiatives, sourcing alternatives, and targeted pricing actions. Taken together, the company expects total cost of goods sold inflation of approximately 7 percent.

Well, Conagra’s cost of goods sold for Q2 was $2.074 billion. If tariffs drive up those costs by 3 percent, that’s an extra cost of $62.2 million; which equals 24.3 percent of Conagra’s net income for the quarter, $256 million. So again, why not try reporting an adjusted cost of goods sold to account for tariffs, and let that flow through to an “earnings before tariffs” adjusted net income? Clearly the amounts involved would be material.

Anyway, as we can see, companies are approaching tariffs disclosure in all sorts of ways — and earnings season has barely begun! Stay tuned.